Study: Microplastic contamination in human brains has increased 50 percent between 2016 and 2024

05/01/2025 / By Ava Grace

- A study in Nature Medicine reveals a 50 percent surge in microplastic contamination in human brains between 2016 and 2024, with brain tissue containing nearly 8 times more plastic than the liver or kidneys.

- Microplastics in dementia patients’ brains were 5x higher than in healthy brains, with sharp plastic shards found near inflamed areas tied to cognitive decline — raising concerns about neurological damage.

- Microplastics (from packaging, clothing, tires, etc.) now permeate air, water, food and human organs. Polyethylene (used in bags/food packaging) makes up 75 percent of brain contaminants.

- Rising dementia rates coincide with plastic proliferation. Microplastics may weaken the blood-brain barrier, trigger inflammation and physically harm brain cells — even in healthy individuals.

- While complete avoidance is impossible, solutions include filtering water, reducing plastic use, improving indoor air quality and supporting detox diets. Policy changes (production limits, biodegradable alternatives) are critical to curb the crisis.

A groundbreaking study has revealed a shocking reality. Microplastic contamination in human brains has surged by 50 percent between 2016 and 2024, with concentrations far exceeding those found in other organs.

In a study published Feb. 3 in Nature Medicine, researchers at the University of New Mexico discovered that brain tissue contains nearly eight times more plastic particles than the liver or kidneys. This finding raises urgent questions about the long-term health consequences of the plastic-saturated world.

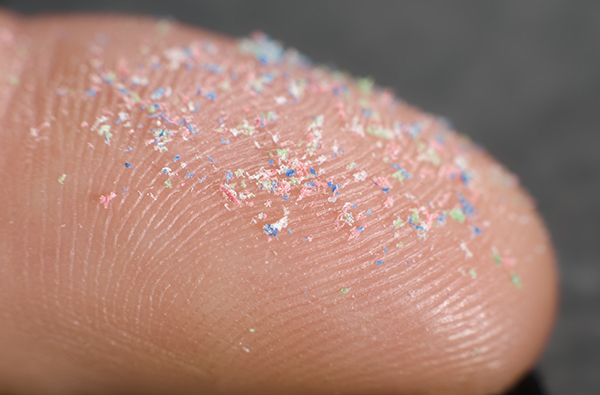

For decades, environmentalists have warned about plastic pollution choking oceans and littering landscapes. Now, the crisis has taken a darker turn: Plastic is infiltrating human biology at an alarming rate. The study, analyzing autopsy samples from 2016 and 2024, found brain tissue contained a staggering 4,917 micrograms (mcg) of plastic per gram, compared to just 433 mcg in the liver. (Related: Microplastics: The silent saboteurs of global food security and human health.)

Even more disturbing? These aren’t just harmless fragments. Electron microscopy revealed razor-sharp plastic shards embedded in brain tissue, some smaller than 200 nanometers. These shards are tiny enough to slip past the blood-brain barrier, the body’s last line of defense for the brain.

Microplastics in the brain and their troubling link to dementia

The study suggested that polyethylene makes up 75 percent of brain contaminants. Polyethylene is the plastic used in shopping bags and food packaging, proof that everyday convenience has a hidden cost.

The most alarming discovery came from brain samples of dementia patients. According to the study authors, the plastic concentrations in these samples were five times higher than in healthy brains – reaching 26,076 mcg per gram. These particles clustered near inflamed blood vessels and immune cells, areas directly tied to cognitive decline.

While researchers caution that correlation doesn’t equal causation, the implications are impossible to ignore. If microplastics are accelerating neurological damage, the consequences for public health could be catastrophic.

Plastic production has exploded since the mid-20th century, with global output now exceeding 300 million tons annually. Microplastics – particles smaller than five millimeters – come from degraded bottles, packaging, synthetic clothing and even car tires. They’ve been found in air, water, food, human blood, placentas and now the brain.

This isn’t just an environmental issue – it’s a public health emergency. Rising dementia rates, now the seventh leading cause of death worldwide, coincide with the plastic boom. While lifestyle factors play a role, the study’s findings demand scrutiny.

The blood-brain barrier weakens with age and disease, potentially allowing more plastic infiltration. But even healthy individuals aren’t safe. Microplastics trigger inflammation, disrupt hormones and may physically damage brain cells.

Eliminating exposure is impossible, but reducing it is critical:

- Filter water: Reverse osmosis systems remove microplastics better than standard filters.

- Avoid plastic packaging: Opt for glass or metal.

- Dust and ventilate: Indoor air carries microplastics from furniture and fabrics.

- Support detox: Foods like cruciferous vegetables and omega-3s may help the body combat plastic toxicity.

Scientists are racing to study plastic’s health impacts, but the solution also lies in policy and innovation – stricter production limits, biodegradable alternatives and better waste management. This study ultimately serves as a dire warning.

With brain plastic levels skyrocketing in just eight years, the time for half-measures is over. If you ignore this crisis, future generations may pay the price with their health – and their minds.

Watch this video about the discovery of microplastics inside human bodies and the damage they cause.

This video is from the Daily Videos channel on Brighteon.com.

More related stories:

STUDY: Microplastics in the body may aggravate cancer and spur metastasis.

Bottled water found to contain alarming levels of plastic particles, microplastics.

Over 90 percent of salt brands contain MICROPLASTICS, scientists find.

Polluted bodies: Researchers find shocking levels of microplastics in CHILDREN.

Billions of microplastics particles are swirling around in the atmosphere.

Sources include:

Submit a correction >>

Tagged Under:

blood brain barrier, brain damaged, brain function, brain samples, Dangerous, dementia, microplastics, Mind, research

This article may contain statements that reflect the opinion of the author