A VICTORY for informed consent: CDC panel reverses decades-old newborn vaccine policy

12/09/2025 / By Willow Tohi

- A CDC advisory panel voted to end the universal recommendation that all newborns receive a hepatitis B vaccine within 24 hours of birth.

- For infants born to mothers who test negative for hepatitis B, the decision is now one of “individual-based decision-making” between parents and doctors.

- The change follows scrutiny of the vaccine’s necessity for low-risk infants and criticism of its original safety trials, which lasted only days.

- The policy had been in place since 1991, despite hepatitis B primarily being a risk for adults through specific behaviors or from an infected mother at birth.

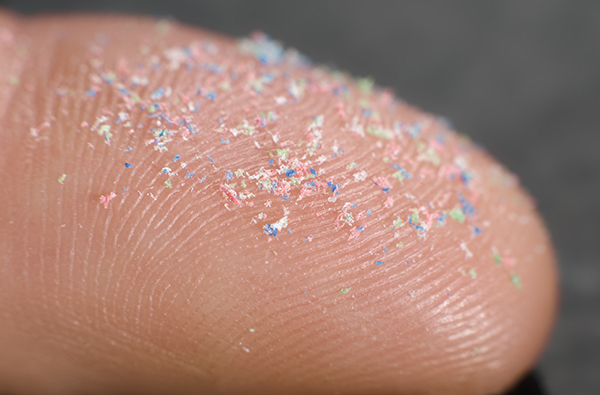

- The vaccine contains aluminum, and critics have long argued the dose given to newborns exceeds safety guidelines for their body weight.

In a landmark decision that recalibrates the balance between public health mandates and individual medical choice, a key advisory committee to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has moved to end a 34-year-old policy requiring virtually all newborns to be vaccinated against hepatitis B within their first day of life. On December 5, the CDC’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) voted 8-3 to recommend that only infants born to mothers infected with hepatitis B, or whose status is unknown, should receive the shot shortly after birth. For the vast majority of babies born to hepatitis B-negative mothers, the committee now advises a model of “individual-based decision-making,” where parents and pediatricians weigh the very low risk of infection against the vaccine’s profile.

The end of a universal mandate built on adult compliance

The policy shift dismantles a cornerstone of the U.S. childhood immunization schedule that has been a source of tension and coercion for a generation of new parents. Since 1991, federal guidelines have directed hospitals to administer the hepatitis B vaccine to all newborns within 24 hours of birth, a practice that became a near-universal rite of passage in maternity wards. The historical justification, however, has long been questioned by health freedom advocates and some medical professionals. Hepatitis B is a blood-borne virus that is primarily transmitted through sexual contact, shared intravenous drug needles, or from an infected mother to her child during birth. For an infant born to a healthy mother, the immediate risk is virtually nonexistent.

Critics have argued the universal birth dose was less about infant health and more about ensuring population-wide vaccine coverage. As noted in past analyses, health officials in the early 1990s acknowledged that vaccinating reluctant adults was difficult, so targeting newborns became a strategy to ensure a vaccinated cohort. The ACIP’s reversal acknowledges this discrepancy, refocusing the intervention on those truly at risk: the fewer than 0.5% of U.S. infants born each year to hepatitis B-positive mothers.

Safety science under the microscope

The committee’s decision was heavily influenced by a rigorous re-examination of the vaccine’s safety science and the changing epidemiology of the disease. During the meeting, Dr. Tracy Beth Hoeg, acting director of the FDA’s Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research, delivered a striking critique of the original clinical trials that supported the vaccine’s licensure for newborns. She noted the trials had no control groups and followed infants for only five to seven days, a standard she stated would be unacceptable for modern approval.

“This is a historic moment of accountability,” said a health policy analyst who attended the meetings. “For decades, parents were told the science was settled, while the foundational trials were profoundly inadequate by today’s standards. The committee finally acknowledged that we cannot claim strong confidence in the risk-benefit profile based on that old data.”

A central safety concern has been the vaccine’s aluminum adjuvant, used to stimulate an immune response. The hepatitis B vaccine contains 250 micrograms of aluminum. According to longstanding FDA guidelines on parenteral (injected) aluminum exposure, the maximum safe limit is five micrograms per kilogram of body weight per day. For an average eight-pound (3.6 kg) newborn, this equates to approximately 18 micrograms. The birth dose alone therefore administers over ten times this amount. While the body can excrete some aluminum, critics point to research suggesting the adjuvant can persist and contribute to systemic inflammation.

A new framework for parental choice

Under the new recommendation, parents of infants born to hepatitis B-negative mothers are encouraged to consult with their healthcare provider to make an individualized decision. The ACIP suggested that if vaccination is pursued, the first dose could be delayed until at least two months of age, when an infant’s immune and neurological systems are more developed. The committee also recommended that insurers cover antibody testing for children who have started the series, allowing families to check for protection before administering additional doses.

The vote aligns the United States with many other high-income nations, including the United Kingdom and several in Scandinavia, which have never recommended universal hepatitis B vaccination for newborns, reserving it only for infants born to infected mothers or those in high-risk groups. Proponents of the old policy, including vaccine manufacturers and some medical associations, warned that delaying the first dose could lead to missed opportunities and increased infection rates. However, CDC data presented at the meeting showed acute hepatitis B cases had been in decline since the mid-1980s, years before the universal birth dose was implemented, due to improved blood screening and other public health measures.

A turning point in the vaccine dialogue: Restoring autonomy at the beginning of life

The ACIP’s vote is more than a simple schedule change; it is a significant cultural and philosophical shift. It represents a move away from a coercive, one-size-fits-all model and toward a paradigm that respects informed consent, individualized risk assessment and parental autonomy. For over three decades, the hepatitis B birth dose stood as a symbol of top-down medical authority, often administered to exhausted parents under duress. Its reversal signals a growing demand for—and institutional recognition of—transparency, robust safety science and medical choice. This decision may well set a precedent, encouraging a more nuanced and evidence-based review of other long-standing vaccine policies, and reaffirming that the first right of a newborn is to receive medical care tailored to their actual needs, not the logistical convenience of a public health campaign.

Sources for this article include:

Submit a correction >>

Tagged Under:

. vaccines, autonomy, awakening, big government, Big Pharma, CDC, Censored Science, children's health, health freedom, hepatitis B, immunization, infant's health, informed consent, parental choice, pharmaceutical fraud, progress, rational, skeptics, vaccine wars, Victory

This article may contain statements that reflect the opinion of the author